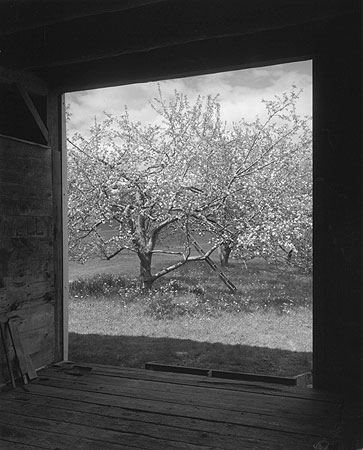

Alfred Stieglitz’s “The hand of man”, circa 1902. The image shows Stieglitz pictorial style, a style of photography that responded to the point of view that photographs could only record. The pictorialist sought to project an emotion through the image through special printing techniques, a playfulness in angles, and other techniques that emphasized aesthetic concerns meant to make a photograph appear like a drawing or a painting. The style peaked in the 1920s. Photo courtesy of Metropolitan Museum of Art

I used two modes of photography for my photo project to represent the three layers of Koreatown’s culture: the static and the lyrical. The following section will describe the work of several documentary style photographers who used these modes as a way to convey information and represent culture and society. One of the major problems to consider before proceeding on a project that uses photography as a means to document is the medium’s nature and its relation to human intention. I will discuss the ways the lyrical and static modes address the problems photography faces as a way to convey information and give representation to people and communities.

In a discussion about photographic representation, Allan Sekula described the camera’s usage in the context of a photographic discourse. Put simply, photographic discourse is in reference to the question, what does a picture provide in the context of a discussion? What is the discussion? He provides several assumptions about the camera’s ability to relay information. For one, he says that a picture is a form of communication. The picture implies a message, which he describes as a “metalinguistic proposition”. For example, “This snapshot represents your son”. The snap of the shutter, he describes as an “utterance” (Sekula, 1975, p. 454). If the snap of a shutter is an utterance of a message, and the discourse represents a discussion, which that message contributes to, then there is an implication of meaning to each photograph if we assume this about all types of photographs.

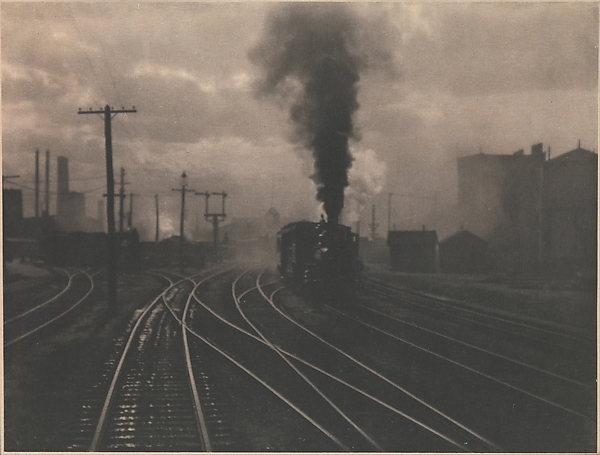

Alfred Stieglitz’s “Steerage”, circa 1907. The image was well regarded by critics as a piece of fine art. Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The way intention becomes complicated by the entry of a discourse is in what he calls “a floating meaning”, an image that has a trivial relation to the subject that was photographed (Sekula, 1975, p. 457). One example he provides is a photograph by Alfred Stieglitz called Steerage. Stieglitz shot an image of two levels of a ship. At the top level, men in blazers and hats look down at a lower level of who Stieglitz refers to as the “common people”, women and children, their clothing hanging from a makeshift clothesline. The image has polemic value as both a statement about class division as well as male patriarchy. However, Sekula argues that incidental polemic value is not enough to secure the message as part of a discourse. Sekula instead looks to statements made by Stieglitz himself about his intention for the photograph: “I longed to escape from my surroundings and join these people… I saw shapes related to each other. I saw a picture of shapes and underlying that of the feeing I had about life… Here would be a picture based on related shapes and on the deepest human feeling, a step in my own evolution, a spontaneous discovery” (Sekula, 1975, p. 464).

At an analytical level, the polemic meaning becomes stripped away by the formalistic qualities of the photograph based on the words Stieglitz provided to describe the image. The abstraction is the meaning of the photo as the catalyst for his “feeling” about the scene. This is reduced to a logical equation: “Common people equal my alienation. We have the reduced metaphorical equation: shapes equal my alienation. Finally by a process of semantic diffusion, we are left with the trivial and absurd assertion: shapes equal feelings” (Sekula, 1975, p. 466). In this example, the meaning of the photo is “floating” between the image’s polemic value and its formalistic qualities. Sekula gives final and conclusive weight to abstraction as the meaning of the photograph, so whatever social outcome the image would have provided becomes incidental. As a staunch absolutist, Sekula adds, “The photographer of genius is possible only through a disassociation of the image maker from the social embeddedness of the image” (1975, p. 469).

Complete dissociation seems impossible and echoes many of the same contentions audiences have about the work of anthropologists who attempt to represent indigenous communities from a “neutral lens”. There is an inescapability the researcher faces with his own cultural lens. However, Sekula’s point was about form taking priority over content. I would argue that both polemics and form were represented in the image, as well as in Stieglitz’s statement, if even as a tertiary consideration. Many critics particularly of the post-modern school of thought believed the social work of Jacob Riis’ How the Other Half Lives ought to have been discounted by virtue of Riis’ sometimes blatant racism and classism exhibited in his texts, calling him a faux progressive (O’Donnell, 2004). Those who argued in his defense asked the audience to look at the social outcomes he produced during his time and the social context he was speaking from, which was much looser about derogatory racial stereotypes. However, what is truly in question is the purity of the photographer’s intention to use the image as a reliable means to a socially beneficial end as opposed to an image acting as an end in itself.

Lewis Hine’s “Setting Eyes on Dolls”, circa 1936. A worker builds rubber doll moulds at a toy factory. The image was part of his project “Men at Work” showing the faces behind the products and infrastructures society regularly took for granted. Photo courtesy of the New York Times

The work of Stieglitz is distinct from the work of Jacob Riis or Lewis Hine. Riis didn’t even describe himself as a photographer. The use of their cameras was strictly a means to an end. Similar but different, Hine had identified as a photographer and even considered photography as an art but not an art for its aesthetic outcomes but rather the photographer’s ability to interpret the everyday world. “He did not mean ‘beauty’ or ‘personal expression’. He meant how people live. He wanted his pictures to make a difference in that world, to make living in it more bearable” (Trachtenberg, 1977, p. 240). These intentions were prefaced by a clear statement of his purpose. In Hine’s project,

Men at Work, he sought to show his audience images of workers, a response to the assumption that cities “build themselves”. He wanted to put a face on the people who work behind the scenes of great American infrastructures. His intention is stated clearly, creating an implied contract of expectation between himself and his audience. The project would provide “a very important offset to some misconceptions about industry. One is that many of our national assets, fabrics, photographs, motors, airplanes and what-not – just happen” (Trachtenberg, 1977, p. 241). Hine makes no reference to aesthetic appeals in his statement, and thus, the purity of his intentions, a polemic statement with strictly social outcomes, are emphasized and can be expected by an audience beyond the level of a “floating meaning” that shares half of its efforts to the creative projections of an “artist”.

Lewis Hine’s “In the Mill” from his Pittsburgh project, circa 1909. Photo courtesy of the Records of the Work Projects Administration

When Hine was working on his project Charities and the Commons in Pittsburg, Trachtenberg said he approached the city as a kind of survey investigator – a social worker or specialist who would comb the city to uncover facts about the ethnic composition of Pittsburgh’s workers, their housing conditions, and family life (1977, p 246). The survey was key for Hine because it provided a structural form for him to work from and a point of view that would provide cohesiveness to his images. It was a reformist’s tool. Trachtenberg said the assumption is that “once the plain facts, the map of the social terrain, are clear to everyone, then change or reform will naturally follow” as had been the case for Jacob Riis who had surveyed the slums of New York. The appeal moved legislators to pass housing reforms that would improve their living conditions by challenging what was thought to be true by providing records of what was actually true (Trachtenberg, 1977, p. 247).

Lewis Hine showed that creative projection shouldn’t be the end in itself but rather, an implicit means to an end. The approach Riis and Hine took made an ethical statement that aesthetics ought to be strictly in service to polemics, that the image was simply a tool, and the true nobility of “art” was its contributions to a discussion on the human condition. Eugène Atget was another social documentary style photographer who demonstrates this point. His work has been described as possessing a particularly arresting visual quality, moodiness and tone that could be described as “art”, but Atget like Riis and Hine worked with clear intentions in mind. Atget’s photo documents of pre-modern Paris arrived from the perspective of preservation. Atget began working decades after the rebuilding process during the beginning of the 20th century. By this time, preservationist groups banded to form conservation establishments for the historical districts of Paris to which Atget was associated (Westerbeck and Meyerowitz, 1994, p. 108).

Eugene Atget’s “Coin de la Rue Valette et Pantheon”, circa 1925. The image show’s an empty street leading to the Pantheon in Paris during its transition to modernity, part of Atget’s catalogue of the city during its transformation. Photo courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art

Atget was said to have approached his subject matter with an “attitude”, revealed in his pictures. (Westerbeck and Meyerowitz, 1994, p. 109). Many of the old Parisian districts were emptied describing them as a “necropolis, a city from the past inhabited by ghosts” (Westerbeck and Meyerowitz, 1994, p. 110). Atget’s viewfinder camera worked with a long shutter speed that blurred the motion of subjects crossing its plane contextualized in literary terms as a “disparity between the slow times of the city” (Westerbeck and Meyerowitz, 1994, p. 110). They were considered technical flaws in the photographs that reflected his feeling of wandering old Paris, places where he once lived, with a sentimentalism and attitude that defined his work as “romantic”.

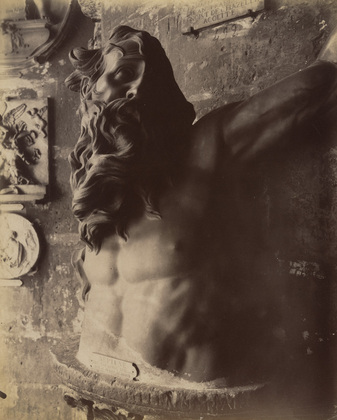

Although his work could be described extensively for its formalistic qualities, its sense of “attitude”, and “sentimentalism”, the latter going against the typical aims of social documentary style photography, his intentions were not for self-serving posterity in itself. However, as Paris was disappearing, he sought to document what would be gone forever. His own feelings of sentimentalism seep into his documents as a statement for the inescapability of the subject from the creation. This is how we can talk about formalism without straying from polemics, but Atget never considered what he was doing was for art as an end in itself. For example, he would sell an image of a lion with two serpents in its mouth to metalworkers who used the references to produce bronze replicas (Hamburg, n.d.). His approach and feeling was sentimental but his intent was to serve the collective memory of those who lived in old Paris. He described his work as documents – an artifact with the specific purpose for providing evidence for something within a discourse. The bulk of his photographs went to visual use for painters and libraries. His stated aim was to catalogue (Hamburg, n.d.).

Eugene Atget’s “Cluny, Neptune, 18th century Spanish art”, circa 1911. Atget photographed several artifacts throughout old Paris, creating a catalogue for libraries and people seeking to create replicas of the old sculptures. Photo Courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art

The work of Atget was said to have a lyrical quality concerning how he captured his cityscapes, architecture, and artifacts he found roaming the streets of Paris, a quality of moodiness or romanticism that emerged from his subjects. The ghost like qualities that appeared from his camera’s slow shutter speeds reflected the emptiness of the old Paris’s streets. How he took his pictures made a statement about what the city was like, its lyrical qualities. Walker Evans said the value of Atget was in his ability to select details, the ones most poetic (1964, p. 108). However, Vescia notes that the documentary photographer is “literary without knowing it, because it is no more than a document of contemporary life captured at the right moment by an author capable of grasping that moment” (2014, p. 17). Put differently, when Weaver described the lyrical qualities of John Szarkowski’s subject matter, namely rural and urban landscapes, people, and architecture, she said the lyrical beauty was in “the way the light is reflected on a barn in the afternoon light, or the way the meadow looks when you walk into it, or the way the light in the sky enunciates the leaves in the trees, all offering a sense of the gorgeousness of what you can see” (Weaver, 2005). These secondary details about the subject matter point to the texture and quality of the subjects photographed as its lyrical characteristics.

Susan Sontag argued that despite the parallel movements between photography and art, the two disciplines oppose each other: the painter constructs, the photographer discloses. Her view is informed by a key assumption about photography. It is a document that discloses a fragment of the world selected by a person’s subjectivity. Thus, artistic considerations are of secondary importance. What piece of the world the photo represents is of primary concern (1977, p. 93). She complicates the point by posing a key question: what piece of the world is it? She believed that until this question was answered, there was no expectation of knowing how to react to a photograph.

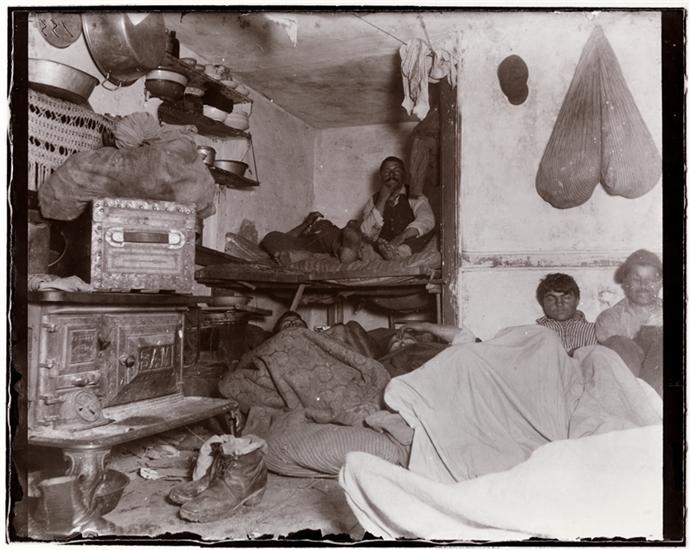

Jacob Riis aimed to produce a document to which photography was relegated to a secondary visual aid. He worked as a police reporter for 22 years and possessed sensitivity to the exploitation and congestion in the living situations of the Irish, Italian, and Jewish people living in New York’s Lower East Side (Westerbeck and Meyerowitz, 1994, p. 241). Riis did not identify as a photographer and had no qualms about making bad images. He wanted his pictures to equal the ugliness he saw in poverty. One image for example is of a cramped crawl space described by its technical flaws.

The focus has been put in the wrong place. Refuse is clear in the foreground, while the band of petty criminals who are supposed to be the subject squat hazily beyond. Yet the photographic mistake puts the social emphasis where it belongs, on the vermin-breeding conditions in which these men live. (Westerbeck and Meyerowitz, 1994, p. 242).

Jacob Riis’s 1889 image of lodgers in a crowded Bayard Street tenement from his book “How the Other Half Live”. Photo courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York

Riis did not have these thoughts in mind when he photographed. He took a run and gun approach, setting his gear and flash in the shadows of the tenement he would be visiting usually without people realizing his presence, snapping off one photo and leaving before anyone got the wiser. The result was satisfying for him. “It is a bad picture but not nearly as bad as the place,” he said (Westerbeck and Meyerowitz, 1994, p. 242). The irony of his non-aesthetic is the emergence of an aesthetic that represents the polemic meaning Riis was after, giving way for his written accounts. The approach for Riis was in service to his statement and thus the purity of his social work remains as the end in itself.

The impact of James Agee and Walker Evans’ classic Let Us Now Praise Famous Men was through the establishment of a clear contextual discourse to which photographs would be of service to, featuring images of portraits, both individual and group, landscapes, and detail shots as a visual archive of how Alabama sharecroppers lived in the 1930s. The images are followed by a detailed account describing the experience, from the point of view of James Agee infiltrating Jim Crow era Alabama farmlands to document how the tenants there lived.

Evans opens the book with his reflection on the attitude of James Agee. “The writing they induced is, among other things, the reflection of one resolute, private rebellion. Agee’s rebellion was unquenchable, self-damaging, deeply principled, infinitely costly, and ultimately priceless” (Agee and Evans, 1988, p. vii). Agee never made a call to find “the truth” about Alabama tenant farmers, instead embracing his own subjectivity to be of service to his social documents. He wanted to represent the truth of his own experience as purely and concisely as possible because his implicit style was the truth that would establish his interpretations. “Those works which I most deeply respect have about them a firm quality of the superhuman… that plane and manner are not within reach, and could only falsify what by this manner of effort may at least less hopelessly approach clarity, and truth” (Agee and Evans, 1988, p. 9). Agee was familiar with the conventions of creative projection, stating that most art transforms reality into “aesthetic reality” in a forward he wrote for Helen Levitt’s book A Way of Seeing, but the kind of images he said photographers should make ought to reflect and record, not transform. He placed the emphasis on developing perception as a way to make an “undisturbed and faithful record” (Agee, 1965).

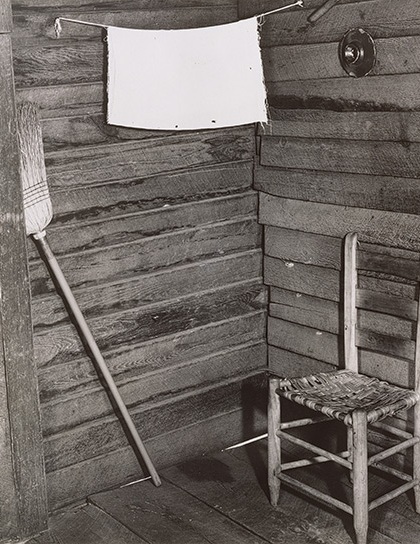

Walker Evans’ static image of a kitchen corner from an Alabama sharecropper’s home. Circa 1936. Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Evans shared the same sentiments. “Photography should have the courage to present itself as what it is, which is a graphic composition produced by a machine and an eye and then some chemicals and paper. Technically, it has nothing to do with painting” (Katz, 1971, p. 364). Evans made the distinction that documentary has a use. In its most literal usage, for example, a police photo of a murder scene may serve as evidence for a crime. He said art in itself is useless. However, he’s also reticent in saying that what he makes is strictly “documentary” preferring to say that he makes art in “documentary style” (Katz, 1971, p. 364).

Agee recognized that even words and documents have a limitation. He would have rather pulled from the roots of the Alabama farmlands a piece of the earth so his readers may come to feel what it was like. “If I could do it, I’d do no writing at all here. It would be photographs; the rest would be fragments of cloth, bits of cotton, lumps of earth, records of speech, pieces of wood and iron, phials of odors, plates of food and of excrement” (Agee and Evans, 1988, p. 10). This was truth for Agee. He wanted his readers to experience the roots of Southern farmland, so people could feel what it was like. Ultimately, the intent of the duo was to inspire a self-reflection in his readers to the things they may take for granted and the people who had no access to the same liberties. “In the hope that the reader will be edified, and may feel kindly disposed toward any well-thought-out liberal efforts to rectify the unpleasant situation down South and will somewhat better and more guiltily appreciate the next good meal he eats” (Agee and Evans, 1988, p. 12).

Walker Evans’s image of the Frank Tengle Family, an Alabama sharecropper family from the book “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men”, circa 1936. Photo Courtesy of the New York Times

Susan Sontag acknowledged that photographers had often enlisted the help of writers to “spell out the truth to which photographs testify – as James Agee did in the texts he wrote to accompany Walker Evans’s photographs in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men” (1977, p. 108). It was the hope of the moralist’s written word that Sontag felt may save photography from the slipperiness of context. She said, “Photography can only say, ‘how beautiful.’ … It has succeeded in turning abject poverty itself, by handling it in a modish, technically perfect way, into an object of enjoyment” (1977, p. 107). The moralists demand that a picture speaks, and it is the caption that tries to provide the missing voice. Sontag acknowledged a commonality between the photograph and the poem. She said, “Poetry’s commitment to concreteness and to the autonomy of the poem’s language parallels photography’s commitment to pure seeing. Both imply discontinuity, disarticulated forms and compensatory unity: wrenching things from their context (to see them in a fresh way), bringing things together elliptically, according to the imperious but often arbitrary demands of subjectivity” (1977, p. 96).

Walker Evans’s image “Alabama Farm Interior”, circa 1936. A static image showing the basic amenities from inside a sharecropper’s home. Photo Courtesy of the Museum of Contemporary Art

The structure of Let Us Now Praise Famous Men and the way the reader must interact with it serves an important polemic function described in the sonata form – a musical convention juxtaposing two musical themes where the second theme is in a different key from the first. The meaning of the song structure is enriched and modified by the second theme thus broadening the range and understanding of the message (Lucaites, 1997). Lucaites argued that the juxtaposition of captionless images that begin the book to a section on Agee’s politics creates a tension that requires an active participation and engagement by the reader. The reader is invited to engage and evaluate the three tenant families who are introduced in the first chapter. Afterwards, the assumptions the reader makes are enriched by Agee’s discourse. Agee’s aim was to decontextualize the experience of poverty as an object of enjoyment. Instead, the images and text work in tandem, fulfilling the shortcomings of the other and addressing the assumptions of the viewer. “The implication here is that Evan’s photographs will serve as a visual, restraining corrective to Agee’s prose, and thus provide a clear balance to the ambiguities of verbal representation” (Lucaites, 1997).

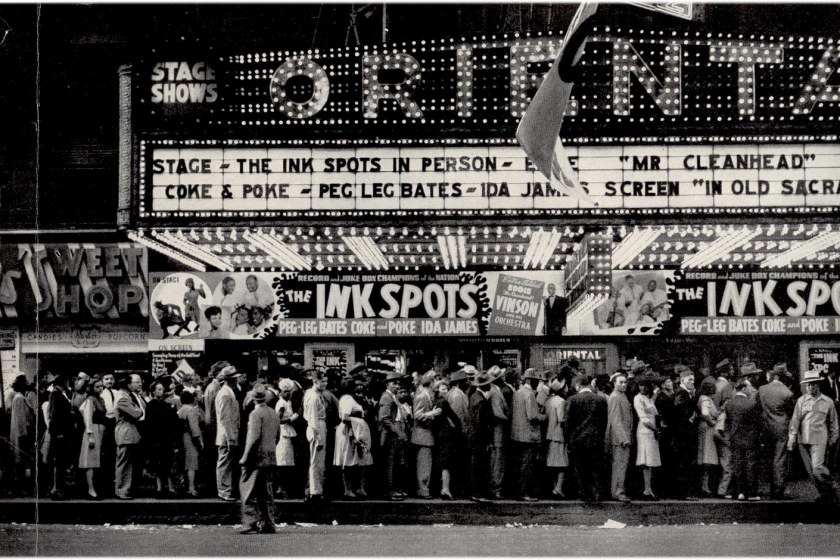

A scene Walker Evans photographed of the Chicago Oriental Theater, circa 1947. Photo courtesy of Binghamton Art History

Many of Walker Evans’s images follow the static mode of photography. One specific example is from a project called Signs. Evans’ series focused on the various signs and advertisements that pervaded the buildings of New York, among other places, during the early and mid-twentieth century. He described America during that time as a place invaded by lettering in every nook and cranny and even in the skylines. One image for example shows three large signs juxtaposed in vertical layers, glowing signs for Lucky Strike, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, and the REV. The choice of cropping cuts the lettering in half to fit a portrait style frame that reads like “concrete poetry”, expressing a “conscious opposition to whatever ‘meaning’ the signs themselves were intended to communicate” (Keller, 1998). The signs are thus re-contextualized beyond the advertisement’s original purposes to convey a polemic statement about the pervasiveness of consumerism. His intent was to challenge an optimism, “urging people to partake in the constant overproduction of goods” during a social context of depression stricken America (Keller, 1998).

Robert Frank shot the common symbols of American life in his photo documentary project The Americans. Two of his leitmotifs were the automobile and the American flag. “The automobile, in whose backseat the Americans of the fifties often had their first sexual experience, becomes a vehicle for Frank’s reflections on love American-style” (Westerbeck and Meyerowitz, 1994, p. 356). The automobile was an outsider’s response to American symbols that responded to a sentimentalism that pervaded popular thinking about photography.

All but one of the seven pictures that end The Americans are of cars (or, in one instance, a motorcycle). Passing from teenagers petting amid parked cars to newlyweds in Reno, a dejected black couple astride a Harley Davidson, and finally Frank’s wife and kids in the Ford, this closing run of pictures has traced a kind of American romance from courtship through marriage to disillusionment and, in the end, the numbness of family life. (Westerbeck and Meyerowitz, 1994, p. 356)

Frank takes the theme of the American automobile to its narrative conclusion as he saw through a type of poetic anthology that contrasted the common image. “Editorially, the shots… disclose a warped objectivity that gives this book its major limitation,” writes one critic (Westerbeck and Meyerowitz, 1994, p. 354).

Howard Becker argued that what makes a photograph “documentary” (or social science or photojournalism) is full context, yet he regards the work of Frank as part of this vein, despite its lack of captions or any statements he makes from The Americans because “the images themselves, sequenced, repetitive, variations on a set of themes, provide their own context, teach viewers what they need to know in order to arrive, by their own reasoning, at some conclusions about what they are looking at” (Becker, 1995). Context in some form of presentation is necessary for an image to be documentary otherwise, he said, viewers will provide their own meaning from their own resources.

For Frank, the polemic statement was implicit and imbedded in his presentation, the types of photographs he chose, sticking closely to thematic motifs like cars, politicians, jukeboxes, and various presentations of the American flag. Frank’s message, the conclusions his photographs made, worked in the form of sequences building from one another.

We learn that a big man is a powerful man (as in Frank’s ‘Bar – Gallup, New Mexico,’ in which a large man in jeans and a cowboy hat dominates a crowded bar), and that a well-dressed big man is a rich and powerful man (‘Hotel Lobby – Miami Beach,’ in which a large middle aged man is accompanied by a woman wearing what seems to be an expensive fur)… We learn that politicians are big, thus powerful, men… We are looking at how the powerful work in some unspecified way. (Becker, 1995).

Becker concludes that had Frank gone farther to expand on his analysis, the images would have functioned more along the lines of visual sociology, leading to a statement about the nature of American politics, among other leitmotifs (1995).

When Tully described the lyrical qualities of Robert Frank’s work from The Americans, she said he experimented with devises such as gesture, movement, light and shadow to capture scenes of back alleys, bus stations, post offices, luncheonette counters, and a variety of other common place establishments and artifacts (Tully, 2009, p. 43). Additionally, Frank also photographed various candid images of people he encountered during his travels who fit the themes he was trying to represent. In a way, Frank was responding with his camera to reactions he would feel from the subjects he would photograph. In an interview for Art in America magazine, Frank described how the lyrical style fit into his own approach to documenting The Americans. “In my photographs what I wanted to photograph was not really what was in front of my eyes but what was inside. That was what made me want to pick up a camera” (Wallis, 1996).

Jon Wagner said invention is part of the tool kit of empirical inquiry and that investigators and reporters exercise some form of inventiveness. The concern is about inventions that bring the viewer closer to or farther away from the truth, inventions, he said, that “get it right” (Wagner, 2004). He adds, “Our choice, in so far as we have one, is not between fact and fiction, but between good and bad fiction” (2004). This is not to say that ethnographic work or the work of documentary style photographers like Frank is untrue. His concern is in reference to invention by the photographer, stating that it’s important to make clear between photographs that mirror the subject and those that reveal the photographer.

The photographers discussed in this section reveal the different issues that can arise in the attempt at representing culture and the human experience. Alfred Stieglitz showed that meaning of an image can float between polemic statements and formalistic concerns, remaining to some, ambiguously represented as either an observation or a creative projection. Lewis Hine’s photographic meaning emerged through the use of a survey component in addition to the photographs he would take. Atget sought to create a catalogue of the artifacts of old Paris that served as a reference for painters and sculptors seeking to create replicas for posterity. He applied the lyrical mode of photography through the use of a slow shutter speed to catch the emptiness of the streets of pre-modern Paris’s cityscapes and architecture. Although, he approached the work with a sense of sentimentality that informed his framing, those considerations were in service to his primary aim of creating records of a disappearing culture. Jacob Riis too used aesthetics to represent his polemic statement. He was sated by an anti-aesthetic and poor composition that served as an after the fact metaphor for the conditions of the slums he photographed. Evans used the static mode of photography to show the way signs had invaded human spaces. His aim was to challenge optimism about consumer culture. Similarly, the work of Robert Frank revealed that a polemic statement could be made by the presentation of photographs in a thematic series. He used the lyrical mode of photography to capture candid scenes of social artifacts and people, many of them in “in-between” moments, seeking to capture some of the isolation he felt pervaded American culture but was seldom addressed.

It was my aim to use photography to show what Koreatown is like and to add to the discussion about its environment as a multiethnic, multiclass part of Los Angeles undergoing a transformation that affects the residents and workers who live there. The following section will describe my process in creating this documentary style project as well as the ways I use the static and lyrical modes of photography.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Agee, J., & Evans, W. (1988). Let us now praise famous men. Boston: Houghton Mifflin

Agee, James. Essay (1989). A Way of Seeing. By Helen Levitt. Durham: Duke University Press, 1989

Becker, H. (2010). Visual sociology, documentary photography, and photojournalism: it’s (almost) all a matter of context. Visual Studies, 10, 5 – 14

Hamburg, M. (n.d.) Atget: the art document photography national gallery of art, Washington.

O’Donnell, E. (2004). Pictures vs. words? Public history, tolerance, and the challenge of Jacob Riis. The Public Historian, 26, 7 – 26

Keller, J. (1998). Walker Evans Signs

Lucaites, J. (1997). Visualizing “the people” individualism vs. collectivism in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. The Quarterly Journal of Speech, 83, 269 – 288

Sekula, A. (1975). On the invention of photographic meaning. V. Goldberg (Ed.). New York: Simon and Schuster, 1981. 452 – 473

Sontag, S. (1977). On photohraphy. New York: Picador

Tully, N. (2009). Looking in: Robert Frank’s “the Americans”. The New Criterion

Trachtenberg, A. (1977). Lewis Hine: the world of his art. V. Goldberg (Ed.). New York: Simon and Schuster, 1981. 238 – 253

Vescia, M. (2014). Depression glass: documentary photography and the medium of the camera eye. London: Routledge

Wallis, B. (1996). Interview with Robert Frank: American visions – photographer and filmmaker. Art in America

Wagner, J. (2004). Constructing credible images. The American Behavioral Scientist, 47, 1477 – 1506

Weaver, J. (2005). John Szarkowski: modern master

Westerbeck, C., & Meyerowitz, J. (1994). Bystander: a history of street photography. Boston: Bullfinch Press